Saturday, October 4th: All Things Zazen

Practice While Walking

Sunday, October 5th: Practice, Practice, Practice

Zero

Monday, October 6th: Zen Metaphors

The Dusty Mirror

Tuesday, October 7th: Zero and the Search For Effective Zen

Episode 15: What Do We Make of the Direct Knowledge Gate?

Wednesday, October 8th: Dogen’s Flower

Aware

Thursday, October 9th: The Dance of a Deeper Explanation

Zen and Koans

Friday, October 10th: All Things Zazen

Beginning Zazen Practice: The Breath and Feelings

George P’s Take: Discourses

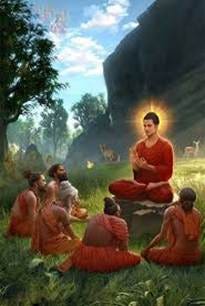

“Do not dwell in the past, do not dream of the future, concentrate the mind on the present moment.” --The Buddha

We at Zen Optimism have been busy “unpacking” Buddha’s First Discourse. The discourses are a central part of our learning in Zen. During his 45-year ministry, the Buddha gave these teachings to monks and laypeople in different locations. Yet some learners wonder, “How do discourses differ from sutras?” Making the answer unclear is the fact that throughout the ages, scholars have disagreed about the correct answer to that question. To wit:

While a discourse is a sermon given by the Buddha (whether written or spoken), a sutra (or sutta) is the written scripture that documents those teachings in a minimal, memorable form. “Sutra” means “thread.”

There are at least 82,000 sutras, and thousands of discourses, with over 10,000 collected in the Sutta Pitaka of the Pali Canon.

The exact number depends on the specific canon and the version of the Sutta Pitaka (the “Basket of Discourses”), with different scholarly editions and commentaries providing different counts for collections.

They are found in the Sutta Pitaka of the Pali Canon that organize discourses by length, theme, or numerical patterns to aid memorization and comprehension, such as the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path, are central to these discourses.

The Three Cardinal Discourses are the first two: The First Discourse, “Setting Rolling the Wheel of Truth” and The Second Discourse known as “The Characteristic of Not-Self”), were delivered to his first five disciples and focuses on the doctrine of anatta (non-self) and asserts that the five aggregates (form, feeling, perception, mental formations, and consciousness) are impermanent, suffering, and not a self, leading to liberation from attachment and suffering when this truth is understood. The third one is “The Fire Sermon” in which he says, “Bhikkhus, all is burning... The eye is burning, forms are burning, eye-consciousness is burning, eye-contact is burning, also whatever is felt as pleasant or painful or neither-painful-nor-pleasant that arises with eye-contact for its indispensable condition is burning.”

Some Important Details Surrounding the Discourses

The power of The Discourses lies in their simplicity, and in their actuality.

After the Buddha’s death, his disciples, led by Ananda, recited these oral teachings at the First Buddhist Council to ensure their preservation.

Key collections of the discourses include the Dīgha Nikāya (Long Discourses), Majjhima Nikāya (Middle Discourses), Saṃyutta Nikāya (Connected Discourses), and Aṅguttara Nikāya (Numerical Discourses).

They are organized numerically, which was an effective way to memorize them in ancient India.

They include a mix of poetic verses, which aid memorization, and prose passages.

They contain myths, history, and folklore, providing a rich window into the world of early Buddhism.

They often begin with “Thus I heard... ”

They often begin with” Bhikkhus,” (Sanskrit, “Beggars”) the monks that are his students

They often are dialogues between the Buddha and his followers.

The “Jesus Sutras” are Christian-Buddhist texts from 7th Century China that incorporate Buddhist terminology and concepts into a Christian framework.

The Take: We feel much gratitude for the Discourses and Suttas because they are a wonderful first step into attaining insight into the Dharma and thus our true nature.